HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE

NEW HAVEN YOUNG MEN’S INSTITUTE

Delivered at the Seventy-Ninth Annual Meeting of the

Association, October 6th, 1904

By the Librarian

WILLIAM ALANSON BORDEN

An Historical Sketch of the New Haven Young Men’s Institute

For nearly a century, the education of the young working man has been more or less of a fad among certain good people, and the decade from 1820 to 1830 was very prolific in organizations for this purpose. I have no desire to belittle this branch of educational work. It was particularly necessary during the decade spoken of, and before. There are many prominent men today who owe their start in life to some of these institutions. They did a good work and they did it with a good purpose, and they are still a cherished memory in the minds of many here.

The Institute was one of them; and it is the object of this paper to explain why, this library, now well along towards its centennial, is still one of the prominent institutions of our city, instead of being only a “cherished memory.”

In the organizations spoken of the instruction was sometimes given in the form of lectures, but more often it was conveyed in classes, after the ordinary public school model. The class-room, from its suggestion of a children’s school, was not always acceptable to the older learner. He was somewhat beyond the school-boy stage, and it grated on his pride, and again, it did not always take him where he wanted to go. He did not want to be taught things so much as he wanted the opportunity of finding out things. What interested him most was not what he ought to know but what he wanted to know. In the class-room he was taught what he ought to know, and he was under control. In the lecture he was more independent; he could listen to what appealed to him and slight what he did not. In a library, when he was so fortunate as to have access to one, he could find out just what he desired. Unfortunately there were but few libraries at this time, and not a great many lectures, and so our young working-man’s search for knowledge usually landed him, perforce, in one of the good people’s class-rooms.

But not all of the educational societies starting at this time owe their inception to the good people before-mentioned. On the evening of the first of August, 1826, three months before the completion of the first railroad in the United States, eight young men, working in New Haven, met at the house of one of their number and formed the Apprentices’ Literary Association. These young men were Charles Kelsey, Albert Wilcox, Joel Ives, Alfred E. Ives, George S. Gunn, Eastman S. Minor, James F. Babcock, and Edward W. Andrews.

But not all of the educational societies starting at this time owe their inception to the good people before-mentioned. On the evening of the first of August, 1826, three months before the completion of the first railroad in the United States, eight young men, working in New Haven, met at the house of one of their number and formed the Apprentices’ Literary Association. These young men were Charles Kelsey, Albert Wilcox, Joel Ives, Alfred E. Ives, George S. Gunn, Eastman S. Minor, James F. Babcock, and Edward W. Andrews.

There is no evidence of any kind patron at hand to set their feet in the right path, and, incidentally, to finance the young society. The evidence of the early record’s points to the fact that they came together from their own initiative, and that what was done was accomplished by their own uninstructed efforts, inasmuch as the weekly meetings all through the summer were devoted entirely to declamations and the reading of original compositions.

In the fall, debating was added to the exercises, new members were taken in, and, the society having outgrown the private house stage, a room was hired in the Glebe Building on the corner of Church and Chapel Streets. In this room the debates were held all winter. At each meeting a composition was read and a piece was spoken, but the stress was always on the debate.

At the very outset a library was started. Few books were to be had, of course, but those few were read, and read at home, as the appointment of a librarian shows.

When the society was a year old they were impressed with the idea that they wanted to receive class-instruction. Several citizens had become interested in them, James Brewster among others, and it is not improbable that some of these good people induced them to give up the instructive debates and take up something more regular. They did not realize, neither did their patrons, that debating instigated the best kind of education, because it was natural and purposeful as well as cumulative.

“…the Institute will do its own good work in the growth and well-being of the city, and in a way that seems to it best.” —William A. Borden

Mr. Stiles French volunteered to teach a class in natural philosophy and the class was formed. It did not last long. Possibly they found too much philosophy and too little nature. Then Mr. George Delwan offered to teach them chemistry, such chemistry as was taught in 1827, and the subject proved so interesting that they kept at it all winter.

By the next summer there were classes in arithmetic, geometry, geography, grammar and bookkeeping. The library contained 65 volumes, and the membership of the society was 42.

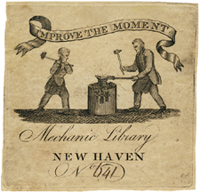

During this summer the society was organized on a good business basis, a constitution and by-laws adopted, a regular board of officers elected, and the name was changed to the Young Mechanic’s’ Institute. Levi Francis was the first president of the reorganized society. Following him, until 1840, were Alfred Walker, Robert H. Osborn, Walter Osborn, John, B. Carrington, Charles Ives, and Sidney A. Tho mas.

mas.

From the beginning, until the second re-organization, in 1840, the Institute led a fluctuating life; but, on the whole, increasing in popularity and usefulness. The classes were kept up, but their life was spasmodic and required constant renewal through the efforts of the executive committee. The lectures were more popular, and consequently more successful as a means of instruction. They were delivered, partly by such men as Henry E. Dwight, Mr. Palmer, Henry White, Professor Olmstead, Leonard Bacon and Professor Silliman, and partly by the members themselves. This latter practice was undoubtedly due to the influence of the Lancasterian School, established at about the same time as the Institute.

The membership varied from 50 to 130, and the library was steadily built up, until, near the end of the period, it had reached 480 volumes.

During this time, as well as afterwards, the Institute was migratory. From the Glebe Building they moved to “Mr. Marble’s building on Church St.,” and thence to the hall occupied by the General Mechanics’ Society.

All the associations like the Institute, formed during the decade spoken of, were based upon the preconceived idea that young men wanted instruction. They did seem to want it, but after it had been furnished, did they continue to want it? Classes starti ng with full benches and soon dwindling away to a non-paying basis indicate something wrong either in the plan itself or in the way the plan was worked out. In other words, did either the instructors, or the before-mentioned good people, or the young men themselves really know what they wanted? The subsequent history of all of these institutions shows that they did not know at the time, and the most of them died before they found it out.

ng with full benches and soon dwindling away to a non-paying basis indicate something wrong either in the plan itself or in the way the plan was worked out. In other words, did either the instructors, or the before-mentioned good people, or the young men themselves really know what they wanted? The subsequent history of all of these institutions shows that they did not know at the time, and the most of them died before they found it out.

Now, the success, and the continued existence, even, of any organization, for whatever purpose,—even these United States of ours, if you will—depends upon the ability of its managers—not its founders, but its managers—to rightly interpret the semi-fluctuating desires of its members and to satisfy those desires. Most of the organizations we are considering started with classes and ended with the remnants of classes, and ended quickly. A few added lecture courses and for that reason lived longer. Here and there one, the Institute among them, keeping their fingers on the pulses of the decades, discovered that what was wanted was not instruction, but the opportunity for independent self-development. These institutions collected adequate libraries, turned their members loose in them,—and lived. The others, one by one, silently folded their tents.

In August, 1840, the Institute was re-organized, and a new constitution and by-laws adopted. Henry White was elected president, the legislature was petitioned for a charter of incorporation, and the name was changed to The New Haven Young Men’s Institute.

By this time the managers had recognized the fact that a regular and permanent membership would never be secured by the educational classes, and if such a membership was to be attained, it could only be done by developing the library and reading room. From this time on, there was where the stress was laid. There was in New Haven; at the time, a collection of several thousand books belonging to the Social Library Co., then practically defunct, that could be purchased, and arrangements were at once made by which this collection would be turned over to the organization as soon as it became a corporate body. This was a considerable business venture, and it called for about all the credit the Institute possessed, but it was a move that took it out of the class of dying institutions, and placed it at once and forever more as one of the permanent factors of our city life.

The charter asked for was granted in 1841, and in August of that year the Institute was formally organized under it, with Dr. John B. Robertson as president. Rooms were taken in the Saunders Building. The books of the Social Library were turned over to it, likewise all the remaining property of the New Haven Athenæum, and Abner S. Beach, the first salaried librarian, placed in charge.

The membership was 350. A list of members would be interesting, but would occupy too much space. Of this 350 we have but one left, Mr. Horace J. Morton, who joined the Institute in 1835. There were a number of life members, and a list of them, containing many well remembered names is appended:

| James Brewster Benjamin Silliman Aaron N. Skinner Benjamin M. Skinner William Dickerman George Walker Benjamin L. Hamlen Samuel J. Hitchcock William W. Boardman Charles L. English Philemon Hoadley John B. Robertson Edward E. Salisbury Atwater Treat Philos Blake Eli W. Blake Charles Peterson Charles W. Hinman John Durrie Philip S. Galpin Robinson S. Hinman, Virgil M. Dow, Roger S. Baldwin Simeon Baldwin |

Timothy Bishop William J. Forbes Henry Peck William McCracken, Jr. John Bromham John W. Fitch John English James T. Mix Timothy Dwight, Jr. Isaac H. Townsend Solomon Collis Henry White Chauncey A. Goodrich Augustus R. Street Nathan Peck, Jr. Charles A. Ingersoll Jonathan Nicholson Simeon B. Chittenden Abraham Bradley Avery C. Babcock A. H. Maltby George Hotchkiss Thaddeus Sherman Theodore Dwight Woolsey |

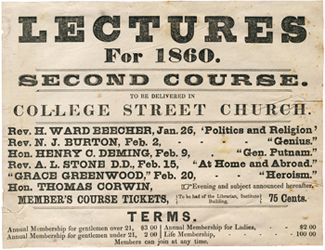

The winter following the incorporation marks the founding of the public lecture course, which lasted nearly thirty years, and which became a large feature of the intellectual life of New Haven.

The second period of the life of the Institute begins in 1840 and lasts until 1856. It bears a close resemblance to the first period. The organization, now a school, a library and a lecture bureau, was a larger factor of the city life. The classes were larger, the library and reading-room were more largely patronized, and its lecture courses dominated the winter programmes; but it still had its periods of depression and financial stress, though worse was to come:

As before, it had many homes. In 1844 it moved to the Temple, on the corner of Orange and Court Streets, and a short time afterwards to the Phoenix Building, on Chapel Street, where it stayed until it moved into its own building.

The presidents during the period were:

| John B. Robertson

James F. Babcock |

Alfred Walker Sidney A. Thomas Charles Robinson Henry Peck O. F. Winchester |

Its directors were the foremost citizens of New Haven. They were:

| John Alley Thomas B. Atwater James F. Babcock Nathaniel A. Bacon Lyman Baird Samuel S. Bassett William W. Boardman Francis Bradley Henry Bronson Moses F. Brown John D. Candee William S. Charnley M. H. Chrysler F. Croswell Charles Durand William H. Elliott, Jr. Charles L. English Alfred H. Ferry John W. Fitch William Fitch Silas Mix Charles Monson Stephen D. Pardee Henry E. Peck Isaac N. Prior George Rice John B. Robertson Charles Robinson William H. Russell Abram Sanford Edward I. Sanford Philo H. Skidmore |

William J. Flagg E. K. Foster Levi Francis Elijah Gilbert, Jr. Daniel C. Gilman John S. Griffing Henry B. Harrison Edward C. Herrick Daniel C. Hinman Robinson S. Hinman Philemon Hoadley Samuel Hooker, John P. Humaston Charles Ives Augustus Jerome Henry W. Jewett Pliny A. Jewett William Johnson Lewis B. Judson Richard F. Lyon William Skinner Henry B. Smith Ralph Smith William H. Stanley Lucius A. Thomas Sidney A. Thomas Henry Wadsworth Alfred Walker Harmanus M. Welch O. F. Winchester John Woodruff |

This list is not entirely complete, as the records from 1846 to 1850 are missing, and there may be a few names unavoidably omitted.

The librarians during the period were Abner S. Beach, George F. Smith, Joseph Downs, Phineas W. Calkins and William E. Baldwin.

In 1856 the Institute received its first considerable donation; Mr. Joseph E. Sheffield gave them five thousand dollars’ worth of the stock of the Northampton Road, the income of which was to be used for the purchase of books for the library. This income has amounted, up to the present time, to sixty-one hundred dollars.

So long as the Institute was a school, the removal from one place to another did not entail a great amount of labor; but by this time the library had increased to some 5,000 volumes, and the work of moving these was considerable, to say nothing of the loss of, membership occasioned by each change.

In the thirty years of its existence it had been constantly on the move and had adapted itself to all kinds of ill-fitting shells. The officers had long wished for a permanent as well as an adequate home. In 1852 we find a movement under way to raise a building fund by private subscription. This was so successful that in 1854 the fund had grown to $13,000, large enough, in the judgment of the trustees, to warrant building. A lot on Orange Street was purchased and the cornerstone was laid of what was thought to be the final home of the society.

In 1856 the building was finished. It was originally known as the Institute Building, but was afterwards better known as the Palladium Building. The dedication was an affair of public interest. The president, Mr. Winchester, gave an account of the former history of the society, mentioning its former homes, and congratulating the members upon reaching their final haven. Addresses were made by Rev. Leonard Bacon, Daniel C. Gilman, and James F. Babcock, and an ode was sung, composed for the occasion by Rev. S. Dryden Phelps. Two days later an inauguration address was given in the Chapel Street Church by Prof. F. D. Huntington, afterwards Bishop Huntington.

The first year in the new building was one of great prosperity. The educational classes had increased to 300, the general membership to 660, and the library to 8,000 volumes.

Mr. Winchester continued as president until 1859, when he was succeeded by Edwin Marble. The whole period from 1856 to 1861 was prosperous. The educational classes diminished, as usual, after the first burst occasioned by the new building and the increased facilities, but the lecture courses fully made up for the decrease in the pupils, and soon became the principal feature in the literary life of the city. A short list of some of the principal lecturers will show why this might well be so:

| Wendell Phillips Henry Ward Beecher Theodore Parker Ralph Waldo Emerson Edwin P. Whipple Herman Melville Thomas Starr King George William Curtis John G. Saxe Grace Greenwood |

Anna E. Dickinson Cassius M. Clay Dio Lewis Artemus Ward Dr. John Lord John B. Gough Edward Everett Josiah G. Holland Rev. T. L. Cuyler Frederick Douglass |

A little friction was developed over some of the lecturers. New Haven was rather conservative in its religion and it had large business interests in the South. A decided exception was taken to some of the utterances of Theodore Parker, Archbishop Hughes, George B. Cheever, Henry Ward Beecher, and Wendell Phillips. After many meetings of the directors and much discussion, a compromise was affected and the names of Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker were dropped from the list of lecturers and goodfellowship was restored.

A little friction was developed over some of the lecturers. New Haven was rather conservative in its religion and it had large business interests in the South. A decided exception was taken to some of the utterances of Theodore Parker, Archbishop Hughes, George B. Cheever, Henry Ward Beecher, and Wendell Phillips. After many meetings of the directors and much discussion, a compromise was affected and the names of Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker were dropped from the list of lecturers and goodfellowship was restored.

Then came the civil war.

The attendance at the lectures and the classes decreased, and the membership fell off.

The receipts from all sources diminished until they were no longer large enough to pay running expenses and take care of the interest on the mortgages, and in 1864 the affairs of the Institute were in such bad shape that the new building was sold to the Home Insurance Co., and the Institute went back to its old quarters in the Phoenix Building, once more a wanderer upon the face of the earth.

With this removal the educational classes were dropped. There was no room for them, and there was by this time little need for them, as the public school system had become efficient.

The lecture courses were kept up for a few years, as they were profitable, and the accumulated income from them finally helped to bridge over the worst period of depression, soon to come.

With 1864 the third period of Institute history closes. The directors during the occupancy of the Palladium Building, from 1856 to 1864, were:

| Lyman Baird John H. Benham Frederick J. Betts Edward F. Blake William S. Charnley Ruel P. Cowles Wilbur F. Day James E. English Hugh Galbraith Daniel C. Gilman Horace P. Hoadley Charles L. Ives William B. Johnson Hannibal I. Kimball Charles Linsley Alexander McAlister |

Horace McFarland Edwin Marble William G. Mitchell Luzon B. Morris Arthur D. Osborne Horatio G. Redfield Abram Sanford Joseph Sheldon Ralph Smith Stephen R. Smith William H. Stanley Lucius A. Thomas Sidney A. Thomas O. F. Winchester John E. Wylie |

From 1864 to 1878 the Institute was mainly engaged in the effort to keep its head above water. It was near sinking, and, strange to say, there were a few who tried to push it down. But it kept up, though to do so required the hardest kind of work on the part of its directors and the utmost loyalty on the part of its friends. It was the only public library in the city. It was, to its friends, the symbol of the intellectual life and well-being of the city, and they proposed to maintain it. And they did.

Among other devices, an appeal was made to the city government, basing the appeal on the grounds that it was a public benefaction, for the use of all citizens, and as such was entitled to public assistance. This was refused. A few years later the city government wanted something, and they were much more solicitous concerning the affairs of the Institute.

Among other devices, an appeal was made to the city government, basing the appeal on the grounds that it was a public benefaction, for the use of all citizens, and as such was entitled to public assistance. This was refused. A few years later the city government wanted something, and they were much more solicitous concerning the affairs of the Institute.

During this period the customary pilgrimages were performed. In 1872 the Institute moved back to the Palladium Building, this time as a tenant. In 1875 the State House opened its doors to it for a few years, but it was finally ousted from there to make way for a museum, and took up its quarters in the Leffingwell Building.

Mr. Marble continued as president until 1869, when he gave place to Ruel P. Cowles. Mr. Cowles served until 1876. He was succeeded by Morris F. Tyler, who, in turn, was followed by Charles E. Graves, in 1877.

The directors during this period of storm and stress are names to be particularly honored by all friends of the Institute. They were:

| James N. Adam Robert E. Baldwin T. Attwater Barnes John H. Benham Charles C. Blatchley Nathan T. Bushnell Watson V. Coe Ruel P. Cowles Jesse Cudworth, Jr. James D. Dewell James G. English George H. Ford Henry W. Foster Hugh Galbraith William S. Goodell Charles K. Gorham Charles E. Graves Abram Sanford John D. Shelley Frank D. Sloat Joseph A. Smith Stephen R. Smith Nehemiah D. Sperry John H. Starkweather |

Francis E. Harrison Albert H. Killam Abram B. Lewis Charles Linsley Edwin Marble George S. Minor Birdsey G. Northrop Minott E. Osborn Henry E. Pardee Ariel Parish Joseph Parker, Jr. Johnson T. Platt Henry J. Prudden Horatio G. Redfield John A. Richardson William C. Robinson William H. Sanborn Abner L. Train Morris F. Tyler Alfred E. Walker Herbert C. Warren Francis Wayland Harmanus M. Welch Roger S. White |

When the Palladium Building was dedicated, Horace Day was the librarian. He served until 1861, when he was succeeded by George A. Blake. In 1864 Mr. Blake gave place to John W. Barber, and he, in turn, to Miss C. Lizzie Todd, in 1869. Miss Todd filled that position for eighteen years.

When the Palladium Building was sold and the tangled affairs of the Institute straightened out, there remained, in the hands of the trustees, the sum of $11,000. This was invested, and the dividends allowed to accumulate, for, much as the Institute needed this income, it could not touch it, under the terms of the trust, unless the main fund were invested in a building.

This fund grew rapidly under the skillful handling of Mr. Welch, and by 1877 it had increased to $20,000. This amount was considered large enough to warrant building again, and certainly the financial condition of the Institute demanded such action. The lot now occupied was purchased, and the building was begun, with Rufus G. Russell as architect.

The building fund has always been managed by the trustees, who fill vacancies in their own board. The personnel of this board since 1852 has been:

| O. F. Winchester Harmanus M. Welch Sidney A. Thomas John E. Earle Ruel P. Cowles |

Pierce N. Welch James D. Dewell T. Attwater Barnes Samuel Lloyd |

The present board is Mr. Lloyd, Mr. Welch, and Mr. Dewell.

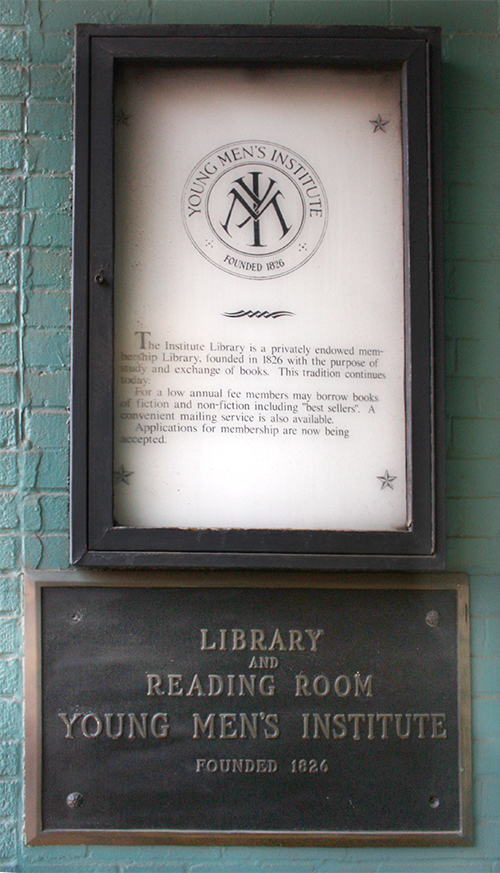

The building now occupied was finished in 1878, and was opened to the public with some formality. The president, Mr. Graves, gave a short sketch of the varied and fluctuating history of the Institute, and addresses were made by Noah Porter, Professor Brewer and Dr. Harwood.

Once in its new home, and, so far as can be seen, its permanent home, the Institute began to consider its position and standing. Its by-laws had already been revised by judge Henry E. Pardee, and the management of affairs placed in the hands of a board of eighteen directors. From this standpoint, the legal one, the outlook was satisfactory, and from this point of view only. The constant changes in residence, with other difficulties, had so reduced the clientage that there were but 16 paying members. There was also a floating indebtedness of $3,500. There were 11,000 books in the library, but most of them were old, and many in bad condition.

Organized efforts were made by the directors to increase the membership, and these efforts were successful.

A committee was appointed, with Major Barnes as chairman, to liquidate the debt. Through their efforts it was reduced to $1,600, and, finally, entirely wiped out.

Many of the older books were rebound and new ones purchased, and by the fall of 1879 the society had started on another period of prosperity, without debt, and with a membership of 626.

During the next year the city government turned its paternal eye upon the Institute, and acting upon its recognized public policy, that all benefactors should be made to pay for the privilege of occupying such an exalted position, it decreed that the new building was liable for taxes.

The legislature was again petitioned and in 1881 granted an amendment to the charter, freeing the library from this burden.

From 1881 to 1884 Major T. Attwater Barnes served as president. It was during his term that modern library methods, crystallized at the library convention a few years before, began to be introduced into the library, although its complete modernization was delayed for a few more years.

It was also during his presidency that the agitation for a free public library was started and the city fathers again turned their attention to the Institute; this time not to tax it, but to swallow it.

The Institute had always been open to the citizens of New Haven. It had always been a public library, but, from financial necessity, never a free one. For years it had been paying out three times what it received from subscriptions, and is doing so to-day, and it would do much more to-morrow were its invested funds increased.

The overtures of the city were received in good part. The directors were ready to make the Institute free, provided the necessary support were guaranteed. They were also ready to join with the city in establishing one large, free library; but when it came to the question of being calmly wiped out of existence, they failed to see the advantage, either to the Institute, or to the citizens at large. The advantage to the third party to the transaction they did not consider a pertinent question.

This agitation continued until 1886, under the presidency of Mr. Graves, elected a second time in 1884. Various committees were appointed by both sides, but no common ground could be found upon which to base an agreement. Finally, in 1886, the directors submitted two plans to the city, which were drawn up by Judge Pardee.

The first plan was that the Institute should lease to the city all its property, for 99 years, at a nominal rent. The city should appropriate a certain sum, annually, for the maintenance of the library. The accumulations of the building fund should be expended upon buildings, which, upon completion, should come under the lease. The library should be free, and should be managed by a board of nine directors, six of whom should be appointed by the city and three by the Institute.

Surely, no proposition could be fairer; or more worth careful consideration, if it were, really, the best interests of the citizens that were being consulted, to the exclusion of various private ones.

The second plan was that the city should pay the running expenses of the Institute, which should be made a free library; that the income from the building fund should be divided into five equal parts, four of which should be expended for books and one for buildings, and that a certain number of the Institute directors should be appointed by the city.

This plan was to enable the city to try the experiment without binding itself for a long term of years.

If at any time, after three years, and before 1896, the city having tried plan two, wished to assume entire control, it could do so under plan one.

This plan did not suit the city. They wanted the Institute to give them everything it possessed, for them to handle as they wished. This the directors did not propose to do. The Institute represented a considerable property, and they represented simply an intention and a charter. And the directors naturally thought that if terms were to be dictated, the dictating should be by them and not by the city. The Institute was in a comfortable financial condition, it was doing a good educational work, and was quite likely to keep on doing it; a good library had been built up and the directors felt entirely competent to manage it during the years to come. As to any probable appointees of the court of common council, they felt less confident.

And so all thought of a union of the two libraries was dropped from serious consideration.

In 1886 Judge Pardee was elected president. It was decided to put the library into complete modern shape and to conduct it for the future under modern methods.

To do this was beyond the ability of the librarian, who had had no experience in those methods. Arrangements were thereupon made with the present writer, at that time lecturing before the School of Library Economy at Columbia, who assumed charge in March, 1887.

During the summer the books were re-arranged on the shelves by subject, and numbered. A card catalogue was begun. A music library of one or two hundred volumes was added. A reference library was opened in the room over the reading-room, and a stairway built connecting the two. An advisory committee of ladies was appointed who held frequent meetings. Mr. John D. Shelley was appointed assistant librarian so that the library could be kept open continuously from 8 a. m. till 10 p. m. A printed catalogue of fiction and music was issued, to fill the demand until the regular card catalogue should be completed.

One year from that time the membership had doubled and the monthly circulation increased 1000 per cent.

In 1889 James D. Dewell was elected president in place of Judge Pardee, deceased. The number of volumes had now increased to 15,000, and all the available shelf room was occupied. It was decided, therefore, to extend the library to the rear. This was done, and the increased room gave a ladies’ parlor and toilet, and allowed the book-cases to be arranged so as to form alcoves, giving a much more social and home-like effect.

Ever since the sale of the Palladium Building and the dropping of all class-room and lecture work, the Institute had been conducted solely as a reference and circulating library. By the time the addition to the building was completed, the new public library had found its feet and the Institute was able to turn over to it all demands for technical and reference books. There was no need for both libraries to keep these books, and as the free library had to buy them, whether the Institute had them or not, the directors thought it better policy to put most of the income into an adequate supply of the books of the day.

Since then the Institute has been conducted along the line of modern literature.

The directors of the Institute, since the erection of the new building, have been:

| Earliss P. Arvine Robert E. Baldwin Amos F. Barnes T. Attwater Barnes William L. Bennett Charles C. Blatchley Peter E. Bowman Edward E. Bradley Ellery Camp Charles E. Cornwall Ruel P. Cowles Samuel P. Crafts Charles E. Curtis James D. Dewell Samuel T. Dutton Willard F. Ensign Frederick B. Farnsworth George H. Ford Joseph R. French Charles E. Graves Francis E. Harrison Thomas Hooker Abram B. Lewis |

Samuel Lloyd Alfred W. Minor George F. Newcomb Henry G. Newton Henry E. Pardee William S. Pardee Ariel Parish Joseph Parker, Jr. Henry S. Peck John A. Richardson A. Heaton Robertson L. W. Robinson Joseph Sheldon John D. Shelley Frederick W. J. Sizer John T. Sloan Charles W. Scranton George H. Sutton John W. Townsend Harmanus M. Welch Pierce N. Welch Roger S. White |

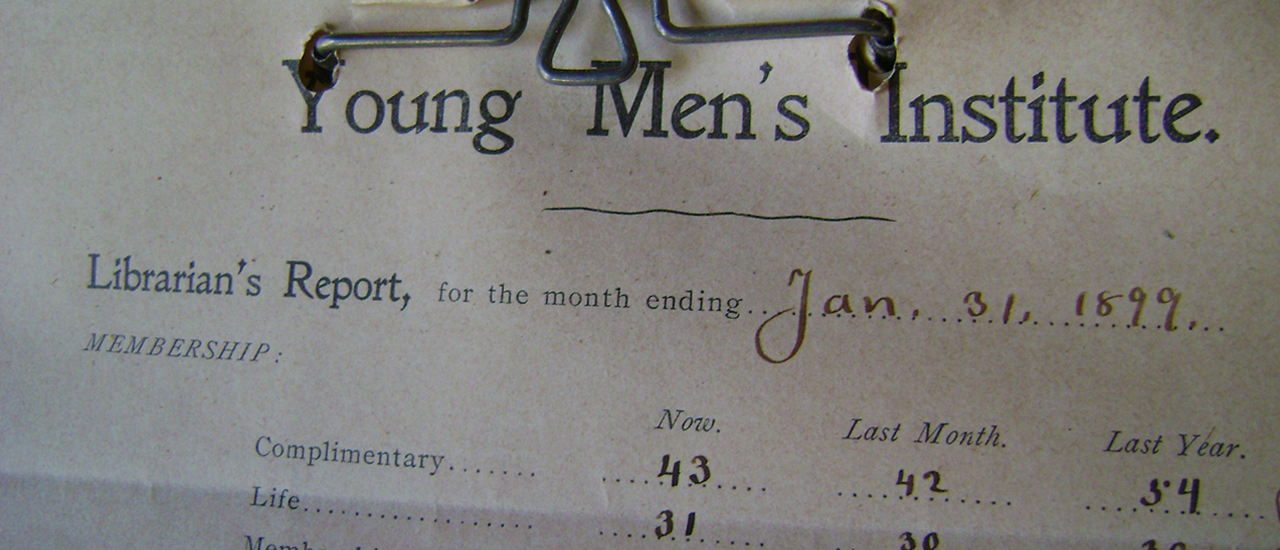

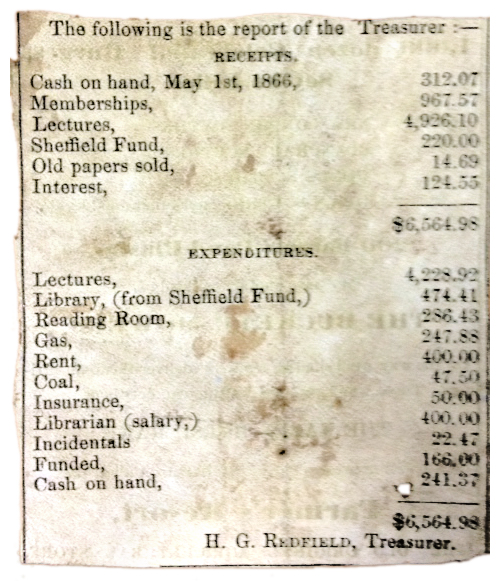

The funds of the Institute now consisted of the following items:

The building fund, amounting to about $50,000.

The Sheffield fund, amounting to about $5,000.

The Gabriel fund, amounting to about $4,000.

The last bequeathed by the will of George Gabriel.

Besides these, the Institute had been named in the will of Philip Marett, for the income from about $60,000, subject to the life interest of his daughter. Upon the death of this daughter, the directors demanded this income from the trustees, and were refused.

Mr. Marett, at the time the will was drawn, was a member of the Institute and a constant visitor; but at this time the association was in the midst of its struggle with adverse fates, and was likely soon to become but a name and a memory. This condition of affairs undoubtedly influenced the peculiar wording of the bequest.

Mr. Marett drew his own will. In it he made the city of New Haven the trustee of this fund, and directed it to pay over the income “to the Young Men’s Institute, or any public library which may, from time to time, exist in said city.”

The court decided that the naming of the Young men’s Institute was immaterial, and that the city might turn the income over to the Free Public Library if they pleased.

And they, naturally, so pleased.

In 1892 Mr. Dewell resigned his office, and Joseph R. French was elected president. Mr. French has filled that position ever since, being unanimously re-elected each year.

This year also marks the establishment of the special loan library. The Institute was the second library in the country to adopt this system, as it was also second to circulate bound music. In some other things it has been first, but in these two it was content to follow the leader.

Many attempts had been made heretofore, by libraries, to solve the new book problem, and to make three books satisfy three hundred people. St. Louis solved the problem. They bought extra copies of the popular books and rented them to members until they had paid for themselves. The Institute did the same. This department has been in successful operation ever since, being patronized by from one to three hundred of the members every month. It is a practical solution of the problem, and the Institute looks for practical rather than theoretic solutions; those who are in a hurry to read a new book can get it at once for ten cents, those who are willing to wait their turn can get it without expense in good time.

In 1894 the librarian was called for a short time to the university library, and his place at the Institute was filled by Miss Stella Williams.

Soon after his return, in 1898, the New Haven Chess Club was organized, and made its headquarters at the Institute. Ever since then the playing of chess has been the principal feature in the smoking room, upstairs, and that room is the chess headquarters of New Haven.

In 1899 the library began to take pupil assistants, who did regular library work, and received instruction in library science. This course covers eighteen months, and fits the pupils for library positions. So far six young ladies have finished the course.

In 1901 the special loan field was invaded by the Booklovers’ Library. The Institute felt called upon to compete, and began delivering special loan books anywhere in the city. The experiment was not financially successful, and at the end of two years, the competition of the Booklovers’ Library no longer being a source of anxiety, the delivery department was closed.

In 1902 the shelf-room was again crowded. To further increase the library meant either to crowd the cases or build another addition, neither of which was desired. The new policy, of making the Institute a collection of modern books on live topics, dictated the sale of the old and unused books, and this was done. Over three thousand were thus disposed of, the reference books were brought down into the reading-room, and all obsolete books were removed from the shelves of the main library and sent “upstairs.”

The future policy will be to send all books upstairs, from the shelves of the main library, as soon as they go out of use. From there they will be sold as opportunity offers.

In conclusion, the history of the Institute and its excuse for being, can be sketched in a few words:

It is, and always has been, a pioneer. Beginning as a school, it fulfilled that purpose so long as the necessity existed; but at the same time, noting the trend of public desires, it had begun to swing into line as a public library and in a few years was doing good work in that line.

So long as a general library was needed it fulfilled that mission, but by the time the new city library was prepared to furnish text and reference books in science, technology and special history, books that a city library must have, to justify public taxation, the Institute, again looking to the future, had become specialized in English and American literature and in biography and travel, and had taken its position as the literary, rather than the educational, headquarters of the city.

To-day, while still holding fast to the library idea, and developing along recognized library lines, it has most of the conveniences of modern club life, both for gentlemen and for ladies.

It is a good general library.

It is a very good modern literary library.

It is a very well equipped and inexpensive literary club.

What the future holds in store for it the future alone knows, but it can be confidently said that in time to come, as in times past, the Institute will do its own good work in the growth and well-being of the city, and in a way that seems to it best.